Safety

Safety

Editor's Review

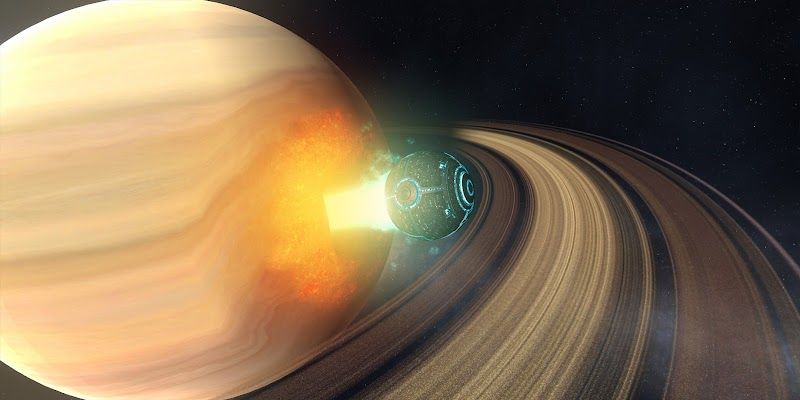

Solar Smash is often referred to as a "planet destruction simulator," but that label really only covers half of what makes it compelling. Beyond the headline mode of pulverizing single worlds, the game hides a more intricate toy box in its System Smash mode, where gravity, orbits, and chained catastrophes make idle tinkering into a surprisingly rich cosmic experiment. The following article is about System Smash and the larger issue of how successful Solar Smash is in balancing eye-candy with an illusion of astrophysical reality. The mode does not only encourage the players to blow stuff up, but to unfold whole miniature solar systems as they adjust orbits, create black holes, and place planets on collision paths.

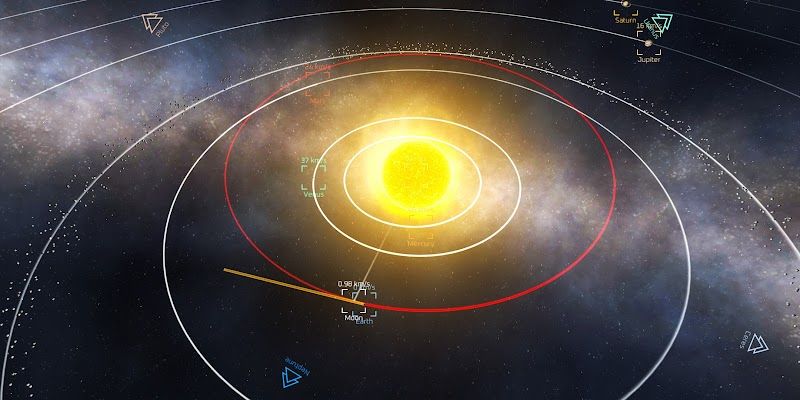

System Smash sets itself apart by giving players a pre-defined version of our Solar System, with extra star systems and empty-slot templates in which to build custom configurations. Rather than the one rotating globe, there is a complete map of planets and moons revolving around their star, all responding to your intrusion. You may, as an instance, bring Jupiter a little nearer to the Sun, and then lean back and watch it with its great bulk sweeping inner planets out of their original paths, and firing them at one another, or at themselves. Since the simulation is going on in real time, the effects of it can be felt over time: initially distorted orbits, then close passes, then the ultimate collisions throwing debris flying through the system. It is quite one thing to watch the system gradually go off-kilter, with a single, carefully considered jostle, and quite another to have a super-weapon blow up a single planet, right after it.

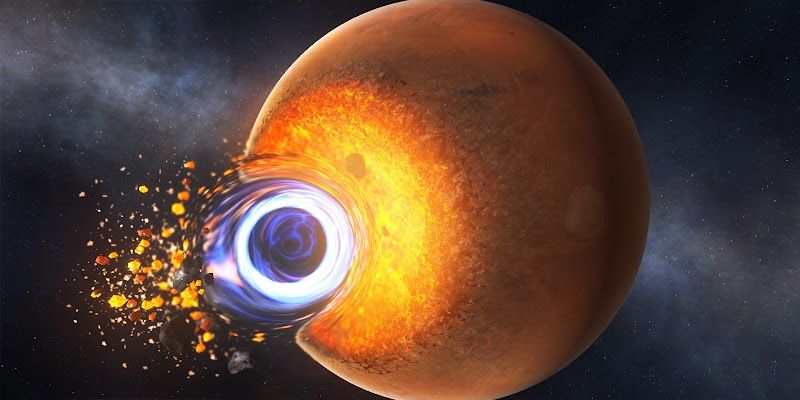

The main benefit of this design is that it transforms destruction into a puzzle of a chain reaction, although the game never puts it in this context. Placing a black hole in the space directly outside the orbit of Mars, it will start pulling the bodies as they travel, shifting them to a tight spiral, and eventually collapses all the systems into the singularity. A star transformed into a supernova engulfs everything nearby, but distant outer planets may initially survive, only to be flung away by the shock wave a few in‑game minutes later. This slow-burn chaos rewards players who enjoy setting up “Rube Goldberg machines” of disaster: altering a single orbit, then fast‑forwarding time to see whether a moon crashes into its planet, or a planet ends up grazing the stellar surface before tearing apart. The pleasure here is partly observational, like watching a physics sandbox, and partly creative, since every outcome is the result of an earlier choice.

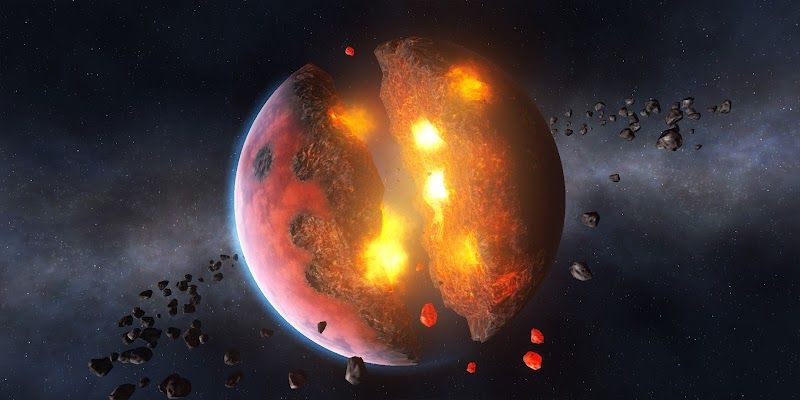

Another strength lies in how System Smash makes space feel larger and more alive than the standard Planet Smash mode ever could. When zooming out, one can see multiple planets in motion at once, with small icons and trails that focus on motion and relationship instead of surface detail. Firing a barrage of asteroids into the inner system doesn't simply create craters - fragments continue on new trajectories to later intersect with other worlds. Over long runs, your once orderly system turns into a messy graveyard of erratic orbits, broken planets, and lone fragments circling a dim star. Scale and persistence imbue even the simplest interactions with a grander context-and there's little quite as satisfying as attempting not just to destroy a single planet, but to orchestrate the slow, theatrical collapse of an entire star system.

Yet, the illusion of realism in System Smash is double-edged, and this becomes one of the mode's key weaknesses: it borrows the visual language of orbital mechanics without committing to strict physical accuracy. Orbits are visibly affected by gravity, but the numerical rules are tuned for spectacle rather than scientific fidelity. Planets can survive close passes and grazing impacts that would be truly catastrophic in realistic simulations, and the time scale is compressed so heavily that events that ought to take millennia play out in minutes. For those players who know even a little real astronomy, certain outcomes feel "off"; tiny changes can sometimes trigger wildly exaggerated reactions, while other obviously destabilizing moves take far longer than expected to matter. This succeeds in yielding a model that looks like real orbital dynamics at first glance but behaves more like a cinematic approximation of the same.

By Jerry | Copyright © JoyGamerss - All Rights Reserved

Comments